I have spent a lot of time thinking about flakiness. That is, after all, what this blog was set up to allow myself. Contradictions, opposition, differences and fleeting thoughts and ideas are increasingly important in my work and my thinking. My last post looked at the contradictions and differences explored in the visual albums of Beyoncé and Terre Thaemlitz. Now I want to consider similar ideas but more generally in audio-visual work.

A combination of two disparate mediums means that these differences and contradictions are inherent in how they relate to each other. In her book Listening to Sound and Noise: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art, Salomé Voegelin quotes Theodor Adorno — who else? — on the benefits of not reducing thoughts and ideas to certainties:

When philosophers, who are well known to have difficulty in keeping silent, engage in conversation, they should try always to lose the argument, but in such a way as to convict their opponent of untruth. The point should not be to have absolutely corrent, irrefutable, watertight conditions – for they inevitably boil down to tautologies, but insights which cause the question of their justness to judge itself.

Voegelin applies this quotation to the way that we place our senses in a hierarchy of worth. Seeing wins, obviously, since seeing is believing. The misguided “certainty” that photography is truth is actually it’s biggest weakest for Voegelin, and our bias for the visual is misguided:

Vision, by its very nature assumes a distance from the object, which it receives in its monumentality. Seeing always happens in a meta-position, away from the seen, however close. And this distance enables a detachment and objectivity that presents itself as truth. Seeing is believing. The visual ‘gap’ nourishes the idea of structural certainty and the notion that we can truly understand things, give them names, and define ourselves in relation to those names as stable subjects, as identities. The score, the image track of the film, the stage set, the visual editing interface, and so on can make us believe in an objective hearing, but what we hear, guided by these images, is not sound but the realization of the visual. The sound itself is long gone, chased away by the certainty of the image.

By contrast, hearing is full of doubt: phenomenological doubt of the listener about the heard and himself hearing it. Hearing does not offer a meta-position; there is no place where I am no simultaneous with the heard. However far its source, the sound sits in my ear. I cannot hear it if I am not immersed in its auditory object, which is not its source but sound as sound itself.

Whilst at university, in that marvellous and much-missed hub of other creative folk, sound was always used in this regard (although without intention). I remember one informal presentation of a stereotypical project about members of some maligned social strata – I want to say it was the homeless, though it could have been any number of things – which was shown alongside a pretentiously melancholic piano piece. Rather than add to the emotive effect of the photographs, it betrayed them in having none. It exaggerated the nauseating untruth of the photographic slideshow projected on the wall in front of us. If only this were intentional, it may have been worthwhile viewing.

This was usually the case when any work was presented with sound. The sound was often misused or employed as an arbitrary dressing for a purely image-based project and this was the problem that I took issue with in my final year at university, producing the project Automatically Sunshine.

The most illuminating response to the project was when I tried and failed to present it verbally pre-installation. It was a horrendous presentation but in hindsight showed that the work didn’t suit the tautological model that all works have to go through to gain critical worth and acceptance. The criticism that stuck out most was “how do you expect your audience to care about your work when you do not tell them what it’s about?” I always remember that question with utter disbelief. The extent to which institutions and the canon have reduced photography to tautology almost made me want to stop studying it.

Voegelin’s introduction voices a number of similar complaints against visual bias and they are worth taking note of. Her proposed philosophy after Adorno is not “irrational or arbitrary, however, but clarifies its intention to embrace the experience of its object rather than replace it with ideas.”

In other words, it does not seek to mediate the sensorial experience of the artwork under consideration through theories, categories, hierarchies, histories, to eventually produce canons that release us from the doubt of hearing through the certainty and knowledge of its worth, which thus render our engagement tautological.

Perhaps it is because of this that sound art is not a mainstream concern. There is no canon. For a moment it felt like there was about to be a sea change — Susan Philipsz won the Turner Prize and the increasing visibility of Chris Watson in mainstream art culture has been brilliant — but it has yet to break through as a dominant and widely accepted form and I hope it never will. The sainthoods bestowed on the likes of the Beatles or John Coltrane are understandable, but they have limited pop, rock and jazz irreparably. The same can be said of photography — this brilliantly irreverent article in Wired comes to mind.

An interesting difference in opinion I have with Voegelin – perhaps a result of our respective biases – is that she sees sound reduced to an arbitrary dressing for the visual. I often think the opposite, when I consider my own interests in the way that record covers are often sidelined to the main aural event and the artists behind them are disregarded in their visual role of enhancing our experiences. Both opinions come from the same desire “to embrace the experience of [an] object” in its totality. Both photography and sound art can be concerned with the phenomenological but students of one rarely consider the other in the depth that they should.

I have my own visual bias – sound is new territory for me and I am a photographer first and foremost – but I do wonder what benefits both types of practitioners would experience if they learnt about the other. Or rather, if photographers learnt more about sound. I’m sure that many sound artists have a knowledge of the visual which is not reciprocated vice versa by visual artists. I feel that a great deal could be achieved if photographers learnt through difference. This is partly the aim of Voegelin’s book: to embrace a sonic sensibility that “would illuminate the unseen aspects of visuality, augmenting rather than opposing a visual philosophy”.

Photographers need to disregard their arrogance over the ease with which they can capture and represent visual events. An event is one thing, an experience is another and the majority of photographers will never adequately capture an experience or provide an audience with a new one if they limit themselves and pander to a needlessly revered canon.

Beyoncé’s self-titled “visual album” has been a much-anticipated pop culture highpoint for intersectionality in a year where feminism and, more specifically, feminist debate and activism has reached a palpable fervour. The album itself was a surprise, but the immediate reaction online was one of relief and “this is what I’ve been waiting for”. It’s a bold and blatantly feminist statement: it isn’t perfect, it isn’t always politically correct, but it is an album that many think was needed.

For all the new feminist movement’s (more than justified) anger and criticism of wider culture — as well as its own problems of flawed universality — here was a moment of sheer joy where women of all races came together and said “This is brilliant.” Not everyone agrees that it is the watershed moment many are claiming it to be but in the year that gave us Robin Thicke and Miley Cyrus, glorifying rape and cultural appropriation seemingly on a loop since the height of summer, here was a pop culture moment that felt like the antidote to a year of shit and that was received with open arms by a united community.

Mikki Kendall brilliantly summarised the feelings of many in her article for the Guardian on the specificity of Beyoncé’s feminism, particularly in her final paragraph:

When we decide that a woman’s personal life (however public) is subject to censure because her choices are not our choices, how feminist are we? When we decide that race, class, or life experiences shouldn’t matter as much as outside opinions, what message are we sending? Feminism is meant to be inclusive. That means not just paying lip service to intersectional analysis, but also embracing the reality that feminist choices vary based on those factors that we don’t all share.

It is this last paragraph that highlights the album’s biggest success for me: bringing the idea of ‘intersectionality’ into the mainstream from a non-white perspective.

Intersectionality is the study of how different systems of oppression and discrimination interact with one another. Not in that victims of racism and sexism are comparable, but how a multiplicity of the two can lead to new issues, problems and experiences – how a black woman and a white woman or a working class woman and a middle class woman experience oppression and discrimination in different ways. We may all strive for equality but an awareness of intersectional issues hopefully prevents any Animal Farm type scenarios of “we are all equal but some are more equal than others.”

The concept of intersectionality is at least 20 years old now but it has been struggling to gain mainstream acceptance and it is through Beyoncé’s insistence on the album being “visual” that this is achieved. The album’s message is not just sound in our ears, disconnected from any visual or broadly cultural anchor: it is visually and aurally rooted in two intersectional cultural specifics – her experiences of being black and a woman.

Feminism strives for gender equality but the debate is far broader in that it explores what it means to be of a certain gender. Intersectionality notes that these gender experiences are influenced by other factors of race, class and sexuality, and it recognises that hegemonic white middle-class feminist ideals are not necessarily compatible for women in all the world’s cultures. The flawed nature of Beyoncé taps into this in interesting ways as Kendall’s article discusses. It takes R&B explicitly back to its source and brings new life to it. It reminds us where this music came from and returns a context that has increasingly been lost in the depressingly homogeneous blob that is a predominantly white – behind the curtain if not in front of it – pop music industry.

It’s also worth nothing that Beyoncé’s sister Solange achieved a similar awareness with her Saint Heron compilation from earlier this year.

Thankfully, this post is not just the forced analysis of a black feminist album by another white male music nerd. I want to dubiously toe the line of intersectionality and explore some comparisons and differences that Beyoncé has with another “visual album” that also explores ideas of relationships, gender and race from a very different angle. The cynical (white male) music press has decried the originality of Beyoncé the “visual album” because — unsurprisingly — she isn’t the first person to make thematically-linked videos for every song on an album, but they have all failed to mention any link that might be seen between Beyoncé and Terre Thaemlitz.

These ideas of intersectionality and the way that Beyoncé channels them arrived at an interesting time for me. One person’s initial reaction in an online debate in the immediate aftermath of Beyoncé‘s release was that, essentially, the album’s message was nothing new and had been expressed better before, in their opinion, by Madonna. This was an interesting choice of comparison in my opinion and immediately my mind went to an album that I discovered just a few weeks before Beyoncé was released: Terre Thaemlitz’ 2008 album Midtown 120 Blues (released under the pseudonym DJ Sprinkles).

At the end of the track Ball’r (Madonna-Free Zone) we hear the voice of Terre Thaemlitz as she describes her experience as a Queer DJ in New York in the 80s and 90s:

When Madonna came out with her hit Vogue you knew it was over. She had taken a very specifically queer, transgendered, Latino and African-American phenomenon and totally erased that context with her lyrics, “It makes no difference if you’re black or white, if you’re a boy or girl.” Madonna was taking in tons of money, while the Queen who actually taught her how to Vogue sat before me in the club, strung out, depressed and broke. So if anybody requested Vogue or any other Madonna track, I told them, “No, this is a Madonna free zone! And as long as I’m DJ-ing you will not be allowed to Vogue to the decontextualized, reified, corporatlized, liberalized, neutralized, asexualized, re-genderized, pop reflection of this dancefloor’s reality!

Thaemlitz makes a very conscious decision on her album to re-contextualize and re-genderize house music. Whilst I cannot say for certain that this was Beyoncé’s intention with her self-titled album, it is certainly something that she achieves. For both Thaemlitz and Beyoncé it does matter if you’re a boy or a girl, it does matter if you’re black or white and, additionally, in Thaemlitz’ case, it does matter if you’re gay or straight, and everything in between those frustratingly stringent categories.

Individual experience is paramount and it is through specificity that we find inclusivity even though that often does not feel like it should be the case. The explicit re-contextualisation of a music genre with the minority group from which it was born may seem like a leap for some and it is probably where the similarities between Beyoncé and Midtown 120 Blues end. There are, however, other works in Thaemlitz’ discography that provide interesting comparative material as I began to discover the more I explored her various projects.

Lovebomb is another “visual album” released by Terre Thaemlitz on her own Comatonse Recordings label in 2005. It is the perfect antithesis to Beyoncé’s own visual album. Whilst the experiences discussed on Beyoncé are specific to the experiences of women of colour, there is a violent side to that culture’s history that she has ignored perhaps because she is very much apart of the machine that perpetuates a certain myth that Thaemlitz, on Lovebomb, explicitly takes issue with.

When Thaemlitz’ visual album begins we see an outdated 16-bit desktop with the words “BOURGEOIS VOUS N’AVEZ RIEN COMPRIS” as its background – bourgeoisie, you have understood nothing. Suddenly the words disappeared under half a dozen or so pornographic pop-ups advertising websites with names like Babes with Boners and Chix with Dix before an error message appears that becomes Thaemlitz’ introductory essay to the project. All this occurs whilst a violently glitched-out, chopped and screwed version of Carole Bayer Sayer’s Come In From The Rain plays in the background.

It is an abridged version of the essay featured on Thaemlitz’ website which reads:

Like any other nation, the House Nation uses a barrage of “love” samples to drown out financial rip-offs, sour deals, embezzlement, exploitation, drugs and organized crime. I do not mean to imply all venue owners, promoters, organizers, performers or others are criminal minded. To the contrary, I submit myself to the generosity and thoughtfulness of many good persons motivated by their various visions of community building. But like taking a controlled substance, the pleasuring vision quest is complicit with an act of imprisoning corruption. The club scene’s deafening plea to ‘love one another’ cannot be separated from the muffled ambiance of happenings behind closed doors.

Pop, country, jazz, soul, R&B, classical… all of these musics overflow with “love,” a term so abundant that we grant it the authority of meaning without inquiry. […] Hollywood’s images of American love’s mannerisms, touches and kisses are visible and profitable around the world. Again, we are quick to grant all of this the authority of meaning – a seemingly unrefutable acknowledgement of (Western) love’s universality. […] If love were truly universal why are individuals’ expectations around partnership so specialized?

This is an intersectionality that goes much further than Beyoncé’s. The “deafening plea to ‘love one another'” that Thaemlitz calls out which “cannot be separated from the muffled ambiance of happenings behind closed doors” feels apt in many respects. The song Drunk in Love seems like a literal embodiment of this “controlled substance” analogy that Thaemlitz employs.

In the online version of the text she concludes:

Rather than songs of love and unity, I long for audio of love’s irreconcilable differences. Not the lovelorn elegy or torch song, but crossed strategies and layered content. Audio in which promise, expectation and momentum are merely possible by-products rather than essential elements. Despite attempts to “get over” past loves, today’s patterns collide with memories of the lost love still longed for, or the bad relationship never to be repeated. New urgent desires are fed by outdated themes, samples and techniques. At risk of invoking another over-used term, I long for songs of “diversity” – conflicted diversity devoid of unity. Such diversity does not threaten a future collapse of contemporary society. Rather, it is a reflection of the long-standing separatism and divisiveness implied in every “holy union” whereby social units break down into cultural microcosms. Empowerment, like love, is when and where you find it. A perverse mirror of the cut.

Beyoncé has her own unique privilege and experience as an awe-inspiringly huge global superstar. The monarchic imagery surrounding her most recent tours is not without irony since the very real dynasty she heads along with husband Jay-Z is probably not even relatable to any actual monarchs, and like many actual monarchs Jay-Z’s most recent album shows that the one-time singer of Hard Knock Life now seems creatively bankrupt and out of touch with reality. These members of the bourgeoisie do seem to have understood nothing. Similar displays of affluence are found throughout Beyoncé but they are juxtaposed against a more aspirational culture. Even when the pimped-out cars rolls out, Beyoncé herself does not blend in with their styling. The social unit has broken despite how much she might strive to return to those supposed roots. That is not to disregard her choice of image and content. It demonstrates different kinds of empowerment for different social classes and in some ways highlights the similarities and differences between them.

Similarly, Beyoncé’s own involvement (or lack thereof) in the production and PR strategies that she, as a person and brand, partakes in are part of the “muffled ambience of happenings” in the background that are inadvertently attached to her visual album. A song like Pretty Hurts cannot be separated from, for example, the fact that Terry Richardson, who’s reputation is completely at odds with the album’s messages, directed one of its seventeen videos. It is hard to believe that everyone involved was ignorant to this and it raises questions of whether this is just one of many disappointing facts of the celebrity life, something that Gaylene Gould addresses here in relation to Lauryn Hill defiantly turning her back on the industry earlier this year and whether artists like Beyoncé should (or even could) follow suit.

Do these conflicts undermine Beyoncé’s apparent intentions? Personally, I don’t think so, but that’s not to say that we should “grant her authority of meaning without inquiry”. Richardson should be damned, universally and without exception. He’s deplorable. The contradictory relationship between Beyoncé and Richardson is one of a number flaws on the album, be they in its production or content, but rather than dismiss it as ignorant or poor because of its lack of a unifying position on various issues, it’s worth exploring those notions of difference further. It has been a persistent theme in hip hop and R&B this year, with Kanye West’s dizzying juxtaposition of Aretha Franklin’s Strange Fruit as a sample and the lyrical content on Blood on the Leaves being the year’s most extreme example.

Strange Fruit is also referenced in Lovebomb‘s liner notes and a similarly disparate combination of samples and lyrical content is demonstrated on its second track, Between Empathy and Sympathy is Time (Apartheid), in which a speech by an unnamed ANC spokesperson on South Africa’s Radio Freedom is auto-tuned to the melody of Minnie Ripperton’s Loving You. What both Kanye and Thaemlitz do here is leave the incredibly violent histories of R&B and hip hop in tact, even if surreally ignored at the same time as in Kanye’s case. Rap music is violent, said its early detractors, but what do you expect of a music that was born out of slavery, racism and oppression.

Cultural forms move, change and shift at an alarming rate. To think how far all modern musics have come in a relatively short space of time is incredible. This makes the fact that cultural contexts are so readily washed away all the more harrowing. Cultural appropriation has been inherent in modern music since its inception. I don’t know of any Delta blues legend who wasn’t exploited or appropriated by white musicians. Even in the middle of the Civil Rights Movement, contexts were disregarded when the Rolling Stones formed and built a 50 year career on the back of cultural appropriation. The music industry has an inherent racism that is seemingly continuing to this day and very few artists have addressed that directly. Kanye West and Lauryn Hill are two notable exceptions in 2013, and hopefully they are the first of many, but Beyoncé has taken a different approach.

A later track on Lovebomb, Anthropological Interventionism, explores this notion of difference in a way that is more relatable to Beyoncé:

Every love song is a work of anthropology. It is an analysis of the physical and mental characteristics, distribution, customs, etc. of people. And, like most anthropological investigations, writing a love song typically begins where it hopes to end – with a conclusion, the parameters of difference, the difference between men and women, etc. As listeners we embrace those songs which affirm our own social patterns through their documentation and validation of our prejudices toward others… tracing the external roots of that bliss or torture in our hearts.

I encourage a more overtly interventionist approach toward writing songs for Lovers. Cast both “universality” and “individuality” to the wayside (never fear, your subjectivity will remain intact). Go into the field. Observe and document the Lovers. Observe and document yourself in that field […] A love song’s persuasive image of universality is its greatest act of mentally invasive violence.

Many of the tracks on Beyoncé have a specificity of experience but the album is not without the universally cherished love songs that Beyoncé is so famous for. Magritte’s famous Lovers in a field are referenced in the video for the song Mine, perhaps the most stereotypically “universal” love song on the album which, visually, is surprisingly surreal and violent with desert explosions, vague allusions to waterboarding and the flaming billboard-sized “MINE” that closes the video. There are love songs here at surface value but much of what Thaemlitz addresses is there too, visibly bubbling underneath.

It’s mostly a co-incidence that I have explored these two visual albums in tandem with one another and together they are continuing to inform each other in fascinating ways. These are just some preliminary thoughts. I do think that, as they have consistently this year on almost every contentious issue, music critics are missing the point when they denounce Beyoncé‘s lack of originality, be that in its presentation or message. I feel that Beyoncé and Thaemlitz may agree on part of the latter’s Red Bull Music Academy lecture from 2010: “The idea of originality has never been important to me. It has always been about referentiality.”

These genres from maligned social groups have always been about referentiality. It is inherent to sample culture, for example, and this referentiality, much like in early sample culture where records were scratched into oblivion, is often a violent act and not one of creative respect. Somewhere along the way, though, this seems to have been mistaken for ignorance. Killing your idols is not the same as or a justification for cultural appropriation. Context is key. The contexts of Beyoncé and Lovebomb are complicated and layered, and they are deeply rooted in the cultural experiences that so much pop would have you forget.

Thankfully, the likes of Kanye and Beyoncé are bringing that back to mainstream culture and they are not alone: Lorde’s hit Royals was another pop revelation for me this year and a great example of killing your idols and re-contextualising pop in relation to class experience, in her case the experiences of a white suburban kid from a no-where town – more relatable to me personally than Beyoncé obviously. Not an uncommon reference point in the grand scheme of things, but the themes on that song and the rest of that album are rare for chart-topping pop like it – personally, I reacted the same to that album as I did when I first heard Through Being Cool.

More generally, all these artists add to the “diversity” of pop culture at large. However, there will always be those who disregard context out of sheer ignorance. In the case of Royals, an appearance on Made in Chelsea – “an eye-opening reality series that follows the lives and loves of the socially elite 20-somethings who live in some of London’s most exclusive postcodes” – is probably about as de-contextualised as you can get since it’s exactly the kinda of popular culture it rallies against.

It’s only a matter of time before Pretty Hurts soundtracks a beauty pageant…

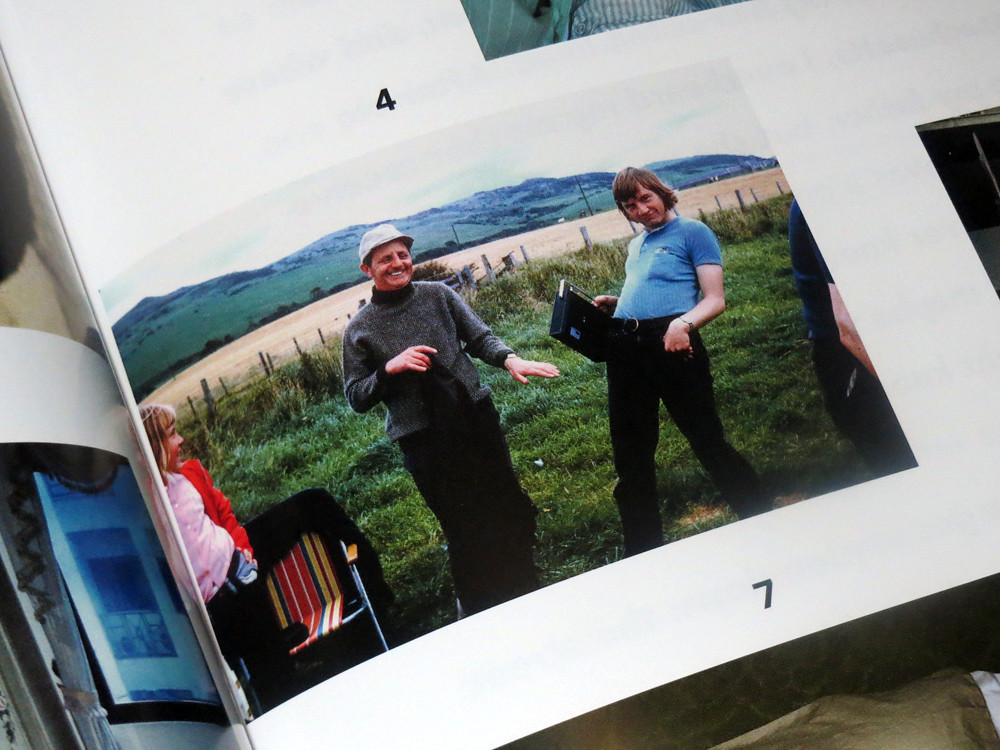

Romka is a magazine where professional and amateur photographers submit their favourite photographs and the stories behind them. I loved last year’s issue so I was right chuffed to be selected for this one.

Issue #8 is available to buy direct from Romka, but if you’re already in the UK it’s also available from the good people at Village in Leeds.

Some of my favourite sounds from the last twelve months. I made this mix at stupid o’clock in the morning and it’s amazing. I might feel differently about it after some sleep but I hope not.