There is a story about William S. Burroughs putting a curse on a diner using a Sony TC cassette recorder.

Burroughs is famous for his pioneering cut-up technique: cutting, editing and rearranging newspaper clippings to form new prose and poetry. Students do this a lot on their fridges now and it’s all over Tumblr. Less practised are his multimedia cut-ups made by arbitrarily recording fragments of television or similarly remixing his own field recordings. They all follow the same basic principles.

The story of the cursed diner goes that after being treated terribly one day by its disgruntled service staff he took up his cassette recorder and, pacing back and forth in front of the diner, recorded the ambient sounds around him. Later, back at home, he cut the sounds from outside the diner with “trouble noises” he had recorded during various negative scenarios to which he bore witness, such as the 1968 Chicago police riots. Chanting and screaming; the ambient sounds of terrible events.

He then returned to the diner, once again pacing up and down the pavement in front of it, playing his new mash-up field recording, channelling the negative energy captured and spliced amongst the ambient sounds of the diner in the hope that this energy would leak back into the world and infect the diner’s atmosphere, and sure enough, or so the story goes, the diner shut down soon after.

This story of a cassette recorder as a “magickal weapon” can be found in Time Mirrors, the autobiographical tenth chapter of the Psychick Bible by Genesis Breyer P-Orridge. He discusses his relationship to William Burroughs as friend, student and collaborator.

What Bill explained to me then was pivotal to the unfolding of my life and art: Everything is recorded. If it is recorded, then it can be edited. If it can be edited then the order, sense, meaning and direction are as arbitrary and personal as the agenda and/or person editing. This is magick. For if we have the ability and/or choice of how things unfold – regardless of the original order and/or intention that they are recorded in – then we have control over the eventual unfolding. If reality consists of a series of parallel recordings that usually go unchallenged, then reality only remains stable and predictable until it is challenged and/or the recordings are altered, or their order changed.

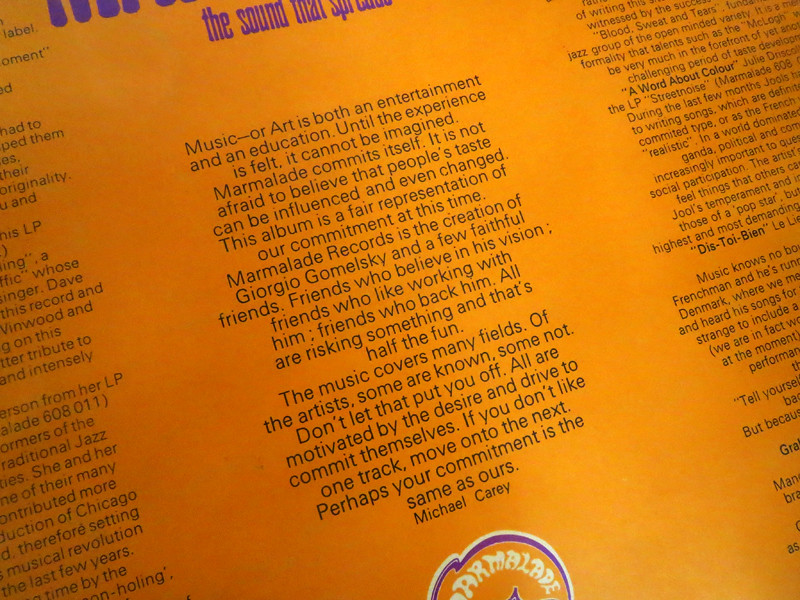

P-Orridge describes Burroughs as using what sounds like a weaponised mixtape with magickal properties. It does not require a great stretch of the imagination to imagine these properties. Mixtapes are an incredibly popular cultural phenomenon and have been for decades. Why? Because there is something about the process that continues to resonate with people, or rather something that comes naturally. It is a phenomenon that has transitioned through technological advances almost seamlessly. No longer is it required to press a RECORD button and edit tape reels or transfer one format to another. (I myself fondly remember the hours spent transfering my favourite songs from my Dad’s record collection onto cassette tapes to play on my Walkmen as a young child, although I doubt I would have the patience to return to that method). Now making mixes can be done digitally and shared via the internet to a potentially global audience at the click of a button. The hard work and over-thought that was initially engrained as part of the creative experience can be completely avoided, if the “labour of love” scenario is not desired.

Mixtapes endure. They already hold a special place culturally, sitting as they do on a broad spectrum that encompasses the mass-produced, commercialised compilations that we buy to the personally crafted gifts and love letters we make to give away. Few other objects can proclaim to share such a territory.

What Burroughs, and in turn P-Orridge, have done is extend the cultural potential of mixtapes. They ground their relationships to this personal cut-up process metaphysically to the world around them and their experiences of and within it – and we are encouraged to do the same. They go beyond the cultural snobbery and reverence that can be found, for example, in the popular book/film High Fidelity where mixtapes are objects to be scrutinised against a set of arbitrary bastardised rules no matter their intended listener or audience. Burroughs and P-Orridge free up the experience itself, focussing on and channelling the all-important emotional intentions first and foremost. Burroughs’ negative intentions towards the diner and John Cussack’s character’s positive intentions towards his girlfriend Laura are not so different, though their attitudes to the craft are polar opposites.

The positive intentions are the most familiar use for us thankfully: either as a soundtrack to a specific time period or event, or as a gift for someone who you wish to instil with positive vibes. In the context of Burroughs’ magickal reimagining it makes the process all the more endearing. We are offered potential mixtapes of mass destruction or potential seeds of love, and all other emotions in between if we so choose. They are released from their shackles of ritualised demonstrations of taste to become something more.

Further still, for P-Orridge and Burroughs the mixtape as form as well as its personal and subjective contexts can serve as a wider metaphor for reality itself.

Concensus reality is […] an amalgamation of approximate recordings from flawed bio-machines. The background of our daily lives is almost the equivalent of a flimsy movie set, unfolding and created by the sum total of what people allow to filer in through their senses. This illusory material world, built ad hoc, second to second, is uncommon to us all. It will only seem to exist whilst our body is passing through it. After that its continued existence is a matter of faith, and our experience of it seeming to have a continuity of presence that seems solid comes from our assumption (only) that we can apparently go back there at some future time of our choosing.

Such is the power of auditory memory that a mixtape can become a map of a remembered reality. Experience envelops each track and falls between the pauses like a fractal. The sounds we hear and remember can be repeatedly shifted from their contexts to be reinterpreted and used again — even mixed again — creating a made mixtape as rhizome that is inseparable from the experiences that surround it. By definition, the mixtape’s potential for “magick” (or magic) is bountiful and, similarly, beautiful.